An Important But Hard LessonWhen I was 7 years old, I had a 2nd grade Language Arts teacher at my neighborhood school in Milwaukee, WI named Mrs. Brown. She was mean. She was one of those teachers that held a strict rule of law in her class, and her students didn’t utter a peep, like EVER, because of it. We were all afraid of answering questions, knowing too well the sting of being accused of not getting it right because we were talking, or daydreaming, or not following directions (all things that are normal for children to do). The consequence of taking a risk to speak could be so severe that it was safer not to speak at all. There was so little joy in her class. In fact, I cannot for the life of me remember learning a single thing that year in her class. I regularly shook in my shoes. I have a distinct memory of feeling humiliated by her insults and severe criticisms so often, that I developed a fascinating strategy to overcome them. Each time I was dealt a berating blow, I would start to count under my breath, almost as if to keep myself from reeling in the dizzying aftermath of one of her insults. I can remember counting, “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10…” And then I’d start again. It was such a strange thing to have instinctually done, but something in me understood that counting might help me keep hold of myself, stay calm, and not break down, cry, and suffer further embarrassment. The part of me hard-wired to be resilient was experimenting with an interesting method to self-soothe and to survive an attack.

After weeks of telling my parents that I didn’t like Mrs. Brown, and asserting that she hated me, one day I came home and shouted out while at the dinner table with my family, “I hate Mrs. Brown!!!!! I hate her, I hate, her, I hate her!” My mother turned to me and snatched me up, and gave me a look that put the fear of God in me (a look I will never forget) and in a piercing, monosyllabic monotone said, “In. This. House. We. Do. Not. Hate.” She let go, my body slid back into my chair, and she went on, “Hate is an evil word. It is a word that causes pain and meanness. Hate does not belong here. It is not allowed in this house. And if you ever use that word again to speak about another human being, I will tear you up from the bottom to the top of this house.”

The irony of that last bit of her response is not lost on me today. YET this is how my Black parents loved and protected me when necessary: with an undercurrent of powerful force. Ta-Nehisi Coates in Between The World And Me, unpacks the complexity of such a tone, that might even be punctuated with a belt or a switch if necessary, describing this tendency toward violent discipline by Black parents of their young: “the violence rose like smoke from a fire, and I cannot say whether that violence, even administered in fear and love, sounded the alarm or choked us at the exit.” Though my mother did not beat me, her words hung in the air, and almost spell-like, they filled the core of my being with a profound new understanding, so she did not have to.

Naturally, I was crushed, devastated, in fact. I felt betrayed by my mother, and felt that she was taking sides in favor of an evil teacher who was torturing me. This was my cry for help and protection, yet I was told that I was not allowed to feel the way I did. Though my cry seemed initially unheard, the resoundingly potent lesson learned on that day at age seven that trumped my personal feelings was this: no matter how arguably and legitimately horrible a human being’s behavior might be, hatred toward that human being is intolerable and absolutely non-negotiable as an option for response. It is useless and only effective at causing more harm. Hate is not a word to be used carelessly or thoughtlessly. On this particular night, I had finally absorbed into consciousness my family’s position on hate after making flip statements about hating this and that frequently enough that my mother felt compelled to clarify it, once and for all. I have never forgotten that lesson.

The Destructive Force of Hate & The Healing Balm of Compassion

If in doubt of my mother’s proverbial warning about hate, the evidence of hate’s destructiveness was unveiled fairly quickly during my childhood. A short time later, my parents let me watch (or I snuck in to watch without permission, I can’t remember) my first film about America’s unique history of Jim Crow racism, Places in the Heart, starring Sally Field and Danny Glover. I cried inconsolably at the horrific images on screen. I remember how my mother hugged me, and the tremendous conflict in her desire to protect me from a real and present danger, lurking in the background our of lives in Milwaukee, in America, and yet her need to expose me to the truth while still in the safety of our home. There my parents could support my journey toward self-awareness and agency through education, conversation, and the arts. My tears and confusion were incessant as I questioned why and how the white people in the film and in America’s past could hate, beat, hang, tar and feather, and burn black people, just because of the color of their skin. My loss of innocence continued, like the slow reveal in a film, and I began to see the full spectrum of life: from the ugly to the sublime and it was like seeing for the first time. And though observing the impact of hate through history pained my heart, a sense of hope and possibility were restored and fueled powerfully by tales of compassion, kindness, and human connection through the childhood literature I read like Sounder, The People Could Fly, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, and I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, to name a few. I began to see the soul, depth and poetry in suffering and its ability to make us feel more and know more, and thereby become more human. I also began to see that hate devoured hateful souls, leaving a lifeless shell, unrecognizable as once human, in its wake.

Self-Reliance & the Pathway to Agency

At a later time, my deep fear of Mrs. Brown was alleviated and the relationship repaired when my parents addressed it formally at a parent-teacher conference. And at dinner that pivotal night, my dad and mom had gone on to inquire about the reasons I felt unsafe with her. This conversation led to my first experience of solitude and contemplation, the kind that yields the cultivation of a fierce sense of independence. Somehow I internalized that I

must look within myself for fortitude as much as I might my parents. My new found understanding that it was possible to control my feelings, and therefore, perhaps my experience of my own life made me more awake. That teachable moment was multi-layered, indeed. Maybe the lesson execution did in fact “choke” me a bit, as Coates suggests, but I learned the lesson. Beyond age seven, I no longer had the luxury of getting swept up in the delusion that my feelings or my state were something I could blame on someone else rather than own for myself.

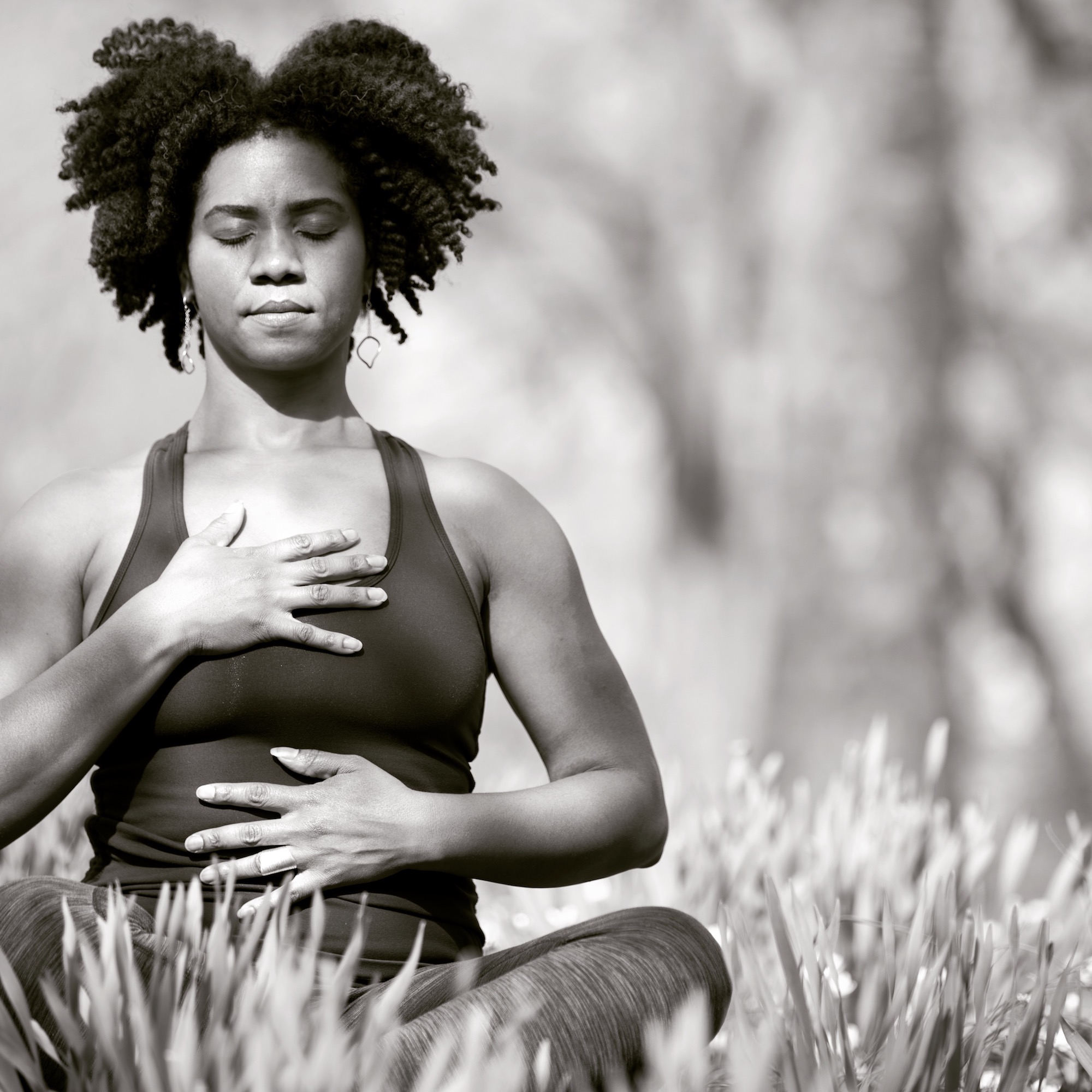

I do not practice hate. It doesn’t even feel right in my bones to try to utter the words towards the legitimately morally derelict that I encounter or see in the media now and again. I have been trained to examine “what’s underneath” by fiercely intelligent and intuitive parents, and by a yoga practice that was first introduced to me by my father in my childhood home. There is always a reason for a person’s behavior, no matter how ugly it is. I may maintain safe boundaries or remain alert with certain people because people always tell you who they are, and it is wise to believe them when they do. But I will not waste my precious energy hating them. Someone once told me that hatred is like swallowing poison and expecting the person you hate to die. These are true words, and I am not done living yet. I am eternally grateful for this difficult lesson on hate. It’s helped me navigate swimming in a society that is more often filled with human sharks than some of us care to admit.

Hate and the Age of Trump

I look to these lessons and wisdom on hate today as I continue to process the election of a hateful man named Donald Trump. His hateful speech toward African Americans, Muslims, women, politicians, Mexican and other brown immigrants is so intense that it feels tangible. While at first, the illogical nature of his hate was puzzling, I remember how similar to temper-tantrum throwing children adults can be when their survival is threatened, even if it is an imagined rather than real death. I saw Donald Trump’s antics on the campaign trail as a cry for help, just like mine was so many years ago. The help I saw coming his way looked more like a great therapist, rather than his assumption to the highest office in the land, however. The rollercoaster of emotions and thoughts I’ve had in response to his election have been revelatory and painful. Yet, I know that the truth will set us free. And somehow, I have empathy for this man and his hate-filled supporters. His parents and their parents failed them all by not teaching them that hatred is tool only for the weak, the lifeless, because it has only the power to destroy and swallow up its perpetrators. Though Donald and his “Alt Right” co-conspirators are crying desperately for help just like I was as a child, what they lack as adults is the cultivation of inner resources (body, breath, and mind) and outer resources (compassionate communication and community building) that support the restoration of a sense of self-determination and agency during challenging times. Their parents and community taught them to blame “others” for their problems, for their own fears, for their own lack of personal power, and to spew the venom of hate at them while at it. Instead of developing self-reliance and self-love, Trump is like many people in America who spew the vitriol of hate because several deep emotional and social needs have not been met or developed in him.

When Human Needs Go Unmet

When people fear death, even when it’s an imagined death, they become irrational. They operate out of their limbic brain and become reactive, aggressive, impulsive and act to ensure short-term survival, rather than take the long view on important decisions. This phenomenon has occurred en masse this past couple weeks, and the backlash – or as Van Jones put it, “whitelash”– that is occurring by a populace whose needs have been completely overlooked will have destructive effects on the quality of life for our entire nation and world. Fifty percent of American voters voted from a place of fear and hate, as opposed to love and consciousness. This is telling. And it isn’t simply telling us that America is full of racists. It’s telling us that our elected leadership, the adults, politicians, teachers, parents, artists, writers, healers, all of us whose role it is to ensure that attention are given to the needs of their communities, have not been the competent, compassionate caregivers to those crying out in need.

When we aim to care for and listen to each other, and address the needs that the crazy-making behavior we’re seeing now is evidence of, we create the capacity for thoughtful, nonviolent speech and action. What is clear about the 2016 presidential election is that Trump’s supporters are pissed and have good reason to be. Healthcare still sucks, though over 20 million people who didn’t have it before now have it. Most American families still do not make enough money to support a family without burning the candle at both ends. Most public schools are a mess because we aren’t investing in our most valuable natural resource: our kids. College graduates are congratulated by a mountain of unforgivable debt, and essentially and invitation to slavery upon completing their education. Healthcare, food, shelter, education are basic human needs, and for many Americans, they are not being met. Not doing so is an inhumane, undignified way to abide in community when we all know that actual resources are in abundance. Many of us, black, white, yellow, brown, and red, drunk the cool aid that there is equal access for all if you just work hard enough, and we feel we have been bamboozled, and refuse to be duped again. The part that pains me and scares most people of color the most: that the disenfranchised will continually be blamed for a socio-economic systemic imbalance that existed long before us, and that ironically we’ve suffered from in the worst ways.

Pleasure Seeking, Pain Avoiding

As a nation, unlike my parents during that fateful dinner, we have avoided teaching these tough, uncomfortable, but critical lessons about America’s history, about the power of love VS. hate, appreciation VS. intolerance, the privileged VS. disenfranchised and entitlement VS. disconnection when those pivotal teachable moments arise with our children and extended family members in our homes, and most certainly in our schools. Instead we watch television, or get on social media, or numb away the nagging sensation of conscience with alcohol, food, or some other poisonous distraction. Our egos would much prefer to run from the pain and discomfort that arises when attempting to explain to your daughter the complex intersection of poverty, race, education, and a history of disenfranchisement for African Americans and how they play a role in her classmate appearing “different” from the other kids at her private school. It may not pleasurable when breaking down the complex circumstances and systems of oppression that inform people’s lives when you drive through a neighborhood that looks “different” from yours, with more people of color, more broken down homes and buildings, boarded up business fronts, and liquor stores to your racist uncle. However, when we lean into these moments and really get curious, educate ourselves and try to address them with integrity and the full historical context that requires examination in order to answer accurately, we plant the seed of empathy, connection, curiosity, openness and kindness within another person. And these are the kind of seeds that will grow. They grow into the willingness to take compassionate action on behalf of the values that make life better for all.

How will you respond to a cry for help from a child or adult when it resembles the sound of hate? How will you prevent hatred from taking root in your heart? At what age and under what circumstances did a lesson about hate take root in your life? How will you talk to your children, nieces, nephews, neighbors, and students about hate? How will we work as nation to uproot this terrible seed that we’ve allowed to spread like a plague?